The Salt of the Earth

A. History of Fission

I

Her lips moved and she said: “The Magic Mountain”, remembers Françoise, the wife of Stan

Ulam, at a bend in the path. On seeing the Hill for the first time.

A large sanatorium set in snow. Immaculate desert of salt vitrified by ice. The blessed arriving one by one. Plucked by an invisible hand.

They stripped bare in the peace of dormitories. United by flesh to the flesh of the labs. And their deported bodies, inhabited by numbers, yielded to the night, pacified.

And so a world would be reborn in pain from its ashes to create other ashes. They gazed at the sky and blessed it.

They still have a Velocar, a pedal-powered automobile.

But this thing is also forbidden to them.

II

Behind them, nations were collapsing. Carnage, cattle cars, conflagration by night, burning ash, flesh. And, far from the fallen towns, revoked childhood had fled their bodies.

Now landless, they were taking over the world. POB one thousand six hundred and sixty-three in Santa Fe. Despite clouds and censors, the rustle of missives occasionally arrived.

Out-of-date, incoherent, mentioning names on the brink of oblivion: Albert, the communist; Auntie Suzanne; André, a survivor; Michel, parachuted to safety. And their mother, deported.

Hidden, enlisted, kept in the cellar, handed over. And we the survivors fulfilled by life. Incredibly young in Los Alamos, where the fashion for Levi jeans began.

In the courtyard, an abandoned car.

Inside, toys, treasures, photos

III

Cliffs, canyons. We crossed rivers and mesas; Indian villages. The ochre of walls, alabaster, blue of the sky. Pines, junipers, ducks returned to the wild.

And the light captured by the Pond. The air feels like champagne, said Stan, drunk on mysteries. Such were the limits, far from human lands, of human knowledge.

Five thousand of the chosen in the hands of secrecy. Mess, cafeteria, dormitory, refectory, laundromat, canteen, army stores. All of them equal by the grace of Groves.

They had children, whose address was given on their birth certificates as POB one thousand six hundred and sixty-three. They came to life and that was all.

Father hidden, at home, under a floor.

Discovered one night. Feet under the curtain. Fear. The scream.

IV

Robert Oppenheimer, alias Oppie, a thin, arrogant, energetic man beneath his fedora.

John von Neumann, alias Johnny the letch. And honourable George Gamow, alias Geo.

Fermi, Stan Ulam, Feynman, Klaus Fuchs, who avoided the death penalty, Leo Szilard, standing stock still in Bloomsbury gazing at the red light, head filled with strange thoughts.

Rabi, Otto Frisch and fiery Teller, already mesmerised by the vast energy of a fireball that would bear his name, depict his face.

Each of them came, like kings, like wise men, bringing their gifts, lemmas or real numbers – everything pooled providentially, the divine blind cost-benefit law.

A large living room with boarded windows.

Plank nailed across the door.

Amado mio/ Love me forever

And let forever begin tonight

Amado mio/ When we are together

I’m in a dream world/ And sweet delight

V

The youth of men and the beauty of women (Françoise again, lost in wonder). Feeling detached from the war, we sampled our first enchilada at the La Fonda bar.

Weighed down by fear and full of grace, they worked hard by day and let their hair down at night at Kitty’s parties. Oppenheimer’s famous martinis.

They played music and put on shows or read poems or watched the Pueblo Indians dancing, swapping masks.

Bella, from the village of San Ildefonso, taught the women the art of making pottery. On horseback, at sunset, end-of-world light. For the world, according to the Mishna, ends each day.

Should we love caretakers or fear them?

The chip pan. The blue water of the laundry tub.

Siempre que te pregunto

Qué, cuándo, cómo y dónde

Tú siempre me respondes

Quizás, quizás, quizás

VI

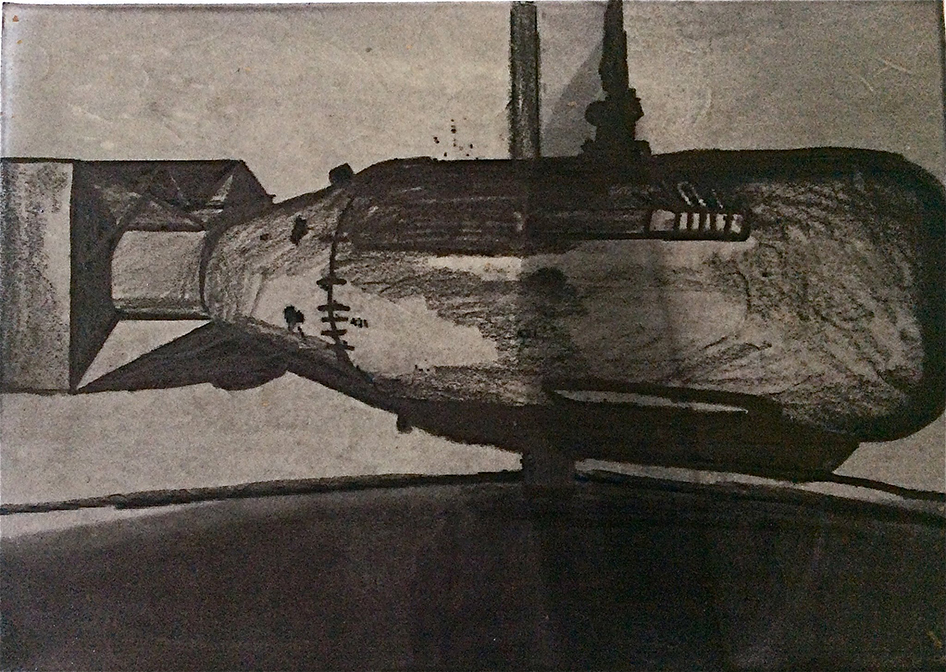

On the morning of 13th July 1945, the Gadget was assembled for the crucial test in the New Mexico desert, at Trinity, named after John Donne.

And, in the afternoon of that day, they inserted the plutonium core – that fickle-hearted loner straying through love and terror – into the metal body of Little Boy

So that it became the obedient Fat Man which would fill the President’s heart with delight. They had to act fast despite their fear and the brewing storm, because on the 16th Truman was to meet

Stalin and Churchill, waiting dumbfounded in Potsdam, in order to become, then and there, the strongest, most powerful of all the Powers that be.

The cellar at night. Potatoes sprouting.

Pluck out the sprouts. Listen to the prayers.

VII

At five-thirty in the morning, the sky caught fire. Flash of white light devouring the ether. The terrific thunder of the shock wave and the stifling heat in the early hours

Terrorised the men buried underground at base camp. Ten million degrees Celsius. The ground a stained glass window covered in gold, a rock of salt raised from the earth. Thirty-two milliseconds later,

A crimson fireball haloed with blue light. Incandescent glow claiming the clouds as far as the pink-tinged stratocumulus. At first like a raspberry, then a goblet,

Then a mushroom in the orange sky, said the spectators of the nuclear dawn, outlandish in their plumbers’ masks. Shielded in their exultation by metaphors and concrete.

Rations of sugar and flour.

A sugar cream pie; the taste of sugar.

VIII

Oppie, who claimed he learnt Sanskrit as he watched the melancholy waters of the Hudson flow by to escape quantum theory and keep his tormented flesh out of harm’s way,

Announced later, displaying the sting of his humble arrogance to the world, that he’d recited to himself, at Trinity, on seeing the flash,

The line from the Bhagavad Gita in which the many-armed god tells Prince Arjuna: “I am become Death, Destroyer of Worlds.”

But no one will ever know what they really felt at the Alamogordo Test Range during the Trinity madness.

Dad, again, but wrong, disguised as a woman.

Wig and necklace, in the strange photo.

L is for the way you look at me

O is for the only one I see

V is very very extraordinary

E is even more than anyone that you adore

IX

(Françoise Ulam remembers) The morning of the day when the bomb exploded (we used to call it the gadget), we were at home, still in bed.

Not invited to the party, but on the alert, watching through the window for a glow, a sound, something coming from the thing, so that something might also come upon us. But there was nothing.

Then, in the evening, Johnny turned up. Von Neumann tired, pale and very shaken. He’d been there and had seen something like the knucklebones of destiny. This incomparable man

Who, as a child, had learnt The Universal History by heart (forty volumes bought at auction), remained among us, like an ordinary man after work. Stunned by his toil.

Reappearance of the stranger among his kin.

Face concealed beneath a veil of tulle.

Don’t be afraid, it’s dad, he’s back again.

Your father, it’s just your father.

X

Later they gathered the surviving sensors. Twenty thousand tons of TNT; one thousand metres levelled. And the calculation of operational parameters to ensure the safety of dropping the bomb

Somewhere, elsewhere, on human cities – Kyoto, Hiroshima, Yokohama, Kokura? – picked by the Target Selection Committee on Von Neumann’s advice.

He was keen to show the authorities that game theory was not just a game and how it could be used to make the world richer. With Flood (the famous Prisoner’s Dilemma),

They discovered that the best way to confuse the enemy’s defence and win the next nuclear war – because this war was now over – was to alternate valuable targets with worthless targets.

A baby arrives unexpectedly, along with unexpected news of death.

They cry, they rush about, everything is in disarray.

XI

Enola Gay, piloted by Paul Tibbetts, took off at dawn on 6th August 1945 from the Tinian base. At a quarter past eight, it dropped its bomb directly over the Shima hospital.

When he got back, Tibbetts received the Cross (and later, they say, went insane). Science, industry and the army working together to achieve the biggest success in history, declared Stimson, Secretary of War.

Three days later, Bock’s Car, flown by Major Charles Sweeney, also took off from Tinian but, because Kokura was shrouded in fog, had to make do with Nagasaki,

Which had momentarily emerged from the mist so that it could drop its bomb on the stadium. The war ended in grand style, justifying the expense committed by Groves before Congress and the Nation.

Niania has returned to the room with the silent piano.

Her black hat, her cloak. She listens to the radio.

XII

In Los Alamos too, it was the end of work, friendship and peace. Despite the whirl of parties and social events, everyone knew they’d have to get on with real life now.

Campus routines and duties in the ugliness of soulless America. And joy was tinged with bitterness. But life had given them everything they’d wished for. By the grace of mathematics and humble technique,

they’d changed art, although they weren’t artists. Lacking religious faith, they’d changed religion. Although not philosophers, they’d changed philosophy. Exiled, stateless,

Lacking territory, roots, land, they’d changed politics. Miraculous survivors far from their slain people, they’d changed death. They were justifiably proud.

Smile though your heart is aching

Smile even though it’s breaking

When there are clouds in the sky, you’ll get by

If you smile through your fear and sorrow

Smile and maybe tomorrow

You’ll see the sun come shining through for you

The camp survivor put up in the shared room.

She speaks at night. The child sleeps.

Pretends to sleep.

XIII

So hard! So hard to do! And yet they took only two years to give mankind the power to destroy this earth which had only taken a so-called omnipotent Creator seven days

To build, rescuing it from chaos. And now chaos rested in their palms ready to escape, like a ladybird cupped in the closed hands of a child one spring morning.

At Oak Ridge, with Tennessee’s pure silver and clear water, the huge Calutron separated uranium isotopes. Unstable U-235 broke free, abandoning its inert brothers.

It was served by twenty-two thousand operatives who, like each of us, acted without knowing the purpose others had attached to their lives.

Sunshine. Open window.

They sing along to the bells.

XIV

In November nineteen hundred and forty-three, the Pile entered a critical state. And, when spring came, rich uranium and, crucially, precious plutonium

Which, kept safe from desire, is not found in nature, were brought to light, leaving their enchanting traces in the sensors’ delicate rapture.

And likewise at Hanford, along the Columbia river, the army and chemical engineers at the Dupont de Nemours factory, which had been in Delaware since eighteen hundred and two,

(and which also manufactured nylon stockings), were thrilled to see the Pile diverge and could, three months later, dispatch a kilo of pure desire sheathed in lead to the Hill.

On the completely deserted boulevard, in summer,

Men run, no one knows where they’re going, or whether they’re in pain.

Then anguish fills the head with heat to the point of collapse.

XV

So everywhere there were men at work. Cities were being built in turmoil. With each new day, the sun rose over the night’s new-born sheds

From which trundled the glorious tanks of the just war, dispersing the black mist of the Great Depression. The uprooted, hobos travelling from station to station on the roofs of carriages,

Saw the light flare with hope. And even black children came back to life in battle or in the shacks of the scattered camps around the factories.

Masses stood straight, like a single man. Millions awoke in the grey dawn of sirens, stretched out on bunks, at the mercy of History’s unknown purposes.

New words, coined from sex and terror. And

The surrendered spirit torn apart.

XVI

In this way, the solitary dreams of dead masters and ancient empires came true. That Power,

Creator and State should merge in a single body governed by Science.

The bodies of Jerusalem, Athens and Rome were mystically united, blurring boundaries between freedom and slavery and, consequently, between love and murder, which eventually became indistinguishable. Inevitably, a god was born to them.

Just as henceforth the fates of Groves and Oppenheimer were merged, one fat, the other thin, bent over a map, deciding where to embody a code, a desire. The central laboratory known as Y.

Then Oppenheimer, determined to disappear, remembered the teenager in the grip of love, running away from the hacienda where a girl… Riding at random across the mesas in a place known as Los Alamos, the bomb factory.

Panic, in the attic, at not seeing her flesh

That had come back to life.

Bésame, bésame mucho

Como sifuera esta noche the ultima vez

Bésame, bésame mucho

Que tengo miedo perderte

Perderte después

Interlude 1: Victory, Joy and the Game of War

It was Admiral Lewis Strauss, a partner at the Kuhn, Loeb & Co. investment bank (described by Green as a very humane man, even though the remark may have been ironic), who had the bright idea of dropping the bomb on old ships allowed to drift at the mercy of the wind, just to see what happened when playing real life Battleships in the middle of the sea. And it was the greatest scientific experiment of all time. Not the end of the world, as predicted by the naysayers. The land consented to suffer. Riddled with pride, catapulted unwillingly into the new era.

Forty thousand people saw the furnace open with their own eyes, committing ships and passengers, rats, pigs and goats to the flames. Millions listened on the radio, deafened by the roar broadcast live. Terrified with happiness, burying the future. And Bikini exultantly entered their peaceful homes, naked and bearing arms from the waters of the Pacific, before lending its name to the arousing bodies of girls striking poses by the sea for the camera lens. First the isolated island, basking in the light of a thousand suns; then the water-loving girls, swimming with the daring of a body stripped bare by a bomb.

A bomb as big as a foot-high picture of Rita Hayworth, said Time Magazine to convey the incredible thing that drew the gaze of millions of human beings, animals and things, and non-existent entities even more powerful than princes, and gods depicted in stone. Entities situated within the structures of power taken from texts exchanged by states, letters of accreditation, numerical codes, and forms used in constitutional law. All of them, whether human or not, separate before and now united in a single living body celebrating victory.

B. A History of Fusion

You came to me

As poetry comes in song

And you showed me

A new world of passion

XVII

Come back, implored Bradbury. Come back to us here, on the Hill. A single bomb and, all at once, a thousand planes will be sent back to limbo, like the war chariots

On which the glory of Rome once depended. When the technology has been mastered, manufacturing will take the place of miracles. Thousands of warheads will emerge from our mechanical fingers.

And the power to stop the course of time, to make time exist, to abolish all life and, consequently, make life exist, will henceforth belong to the fallen on earth, meaning us,

Meaning all men. For who else could have snatched the waste of the mineral ages from the land for their own glory? At last mankind can consent to be. In other words to be, or not to be.

My brother, Jean-Elie, on his way back from school,

free to move, to buy a croissant,

to sit on a bench, in a park.

XVIII

So they went back to Los Alamos. Each of them, in the loneliness of campuses, had invented justifications to restore the force of attraction that would subtract them from the insignificance of works and days.

Some trusted their instincts, forever ruled by science. Others wanted to save the laboratory whose funding was dwindling daily. Or to protect Europe from the Soviets.

Or to return to that state of purity which had joyfully swept over them in the desert. Or to be once again the leaders, the best. Or to show their loyalty to Teller, whose heart was already consumed with love for the Super.

But we have to survive, said Neumann. Because he knew there would be men who have done and will do whatever mankind was capable of doing. And that they were those men.

The yellow star pinned to the top of the Christmas tree.

XIX

So, on the 18th November, nineteen hundred and forty-six, John von Neumann wrote to Teller: I hope the worst is behind you and in front of you, nothing, honestly nothing,

But a happy carefree life on the Hill in Los Alamos. We’re all mad and you’re the worst. Understand the arrogance of my humility. It was an elegant way of voicing

His intense desire to be involved in the H bomb, that crazy, impossible dream of fusion simulating the stars, i.e. the energy setting the universe aflame, whose existence Edward had inferred.

It was a thrilling problem. But no one knew how to calculate the geometric factors, the volumes, the intersections of solids. And sometimes Edward wept with frustration and shame.

First school. There are nuns, frightened all the time.

Kneeling in vain when the scream of a plane

passes overhead in the sky.

XX

The logical way to achieve fusion and make an H bomb is to use a fission bomb as a trigger, i.e. a normal-sized A bomb weighing twenty kilotons (as at Hiroshima).

A billion degrees for little more than a microsecond. And then unprecedented power will surge from the lithium core where tritons and deuterons have fused in the confined space

Of a fairly light casing to be dumped by a B52, or travel the world in a missile, flying over oceans, continents and poles quick as a flash and therefore unpredictable, unavoidable.

But no one really knew how to initiate fusion. Gamow had his theory (known as the Cat’s Tail), and so did Teller. They all applied themselves to the problem, Fermi and Rabi; Ulam and Johnny.

Everything is black and white, newspapers, images,

the Japanese wandering about on the screens.

XXI

Agreement over fission, sealed by the great peace of the real war, was followed, for all their trouble, by disagreement over fusion, nurtured by pride in an unbelievable all-out war.

Edward and Robert filled with hatred, denounced each other like two mimetic brothers. Teller plotted with Strauss to accuse Oppie of plotting to abort

The child of desire, the super Super. And Stan was pursued by Nemesis when, caught up in his dreams, he realised Teller would never succeed in capturing the beautiful monster of the future unaided.

“I found a way to make it work”, said Stan one day to his wife, as he stared into space like a blind man by the window. And, the next day, he went to see Teller.

Waiting in the car in front of the hospital. And at night, when he’s

with the sick. Because my mother will never leave his side again

and because we’ll never leave her side again. As if, yes, as if.

XXII

Because Stan and Johnny had discovered it was possible to apply probability theory to the mechanics of continuous fluids (known as the Monte Carlo method), and thereby manage

To press chance into the service of hydrodynamics. Consider therefore that particles are merely fictions; so sets of integral equations with multiple variables will represent infinite series.

During those blistering days, they happened to subvert the signs, placing the word nebech anywhere in their sentences. One saying cogito nebech ergo sum, and the other cogito ergo nebech sum, to make sure they’d remember they were nothing but dust.

Then Ulam wrote a secret report describing the idea, which Teller commandeered. And they never spoke to each other again, hurt by the idea that truth could be exclusive and so similar to the love that bound them.

But always the same dream in which the sky was filled with strange spaceships,

silently moving towards something unavoidable.

XXIII

On the 31st October, nineteen hundred and fifty-two, for the first time, in Eniwetok on the Marshall Islands, a thermonuclear bomb exploded, proving Teller the optimist, right versus

Oppenheimer the pessimist, who hadn’t wanted to forge ahead. Then, two years later, again on Bikini, a single explosion whose yield was ten times that of the total bombs dropped on Germany previously.

The coral atoll became a cloud of radioactive dust, dispersed by the wind. And the Lucky Dragon disappeared, exposed to radiation whilst sailing familiar seas without ever knowing why a hundred kilotons had ripped through the air,

Setting two hundred kilometres of sky alight, to sacrifice a handful of Japanese fishermen to the world. After that, the strategists explored the ontology of threat, which dissipates as a result of inaction and is neutralised if carried out.

But always the same dream in a vast dwelling, both familiar

and unexplored. Too vast, bare of those who lived there.

Acaricia mi ensueño

El suave murmullo

De tu suspirar.

Cómo ríe the vida

Si tus ojos negros

Me quieren mirar.

Interlude 2: Economic and Technical Fallout

Energy: It was from black Pechblende mined in Joachimsthal, the Silver Mountain, that they extracted an unknown material named Uranium in honour of Uranus, which had just risen in the sky. It was full of polonium and radium, spontaneously radioactive components within which nuclear fission occurred when bombarded with neutrons by Fermi. On the 2nd December, nineteen hundred and forty-two, the reactor diverged for the first time. A heavy nucleus split to trigger a fission chain reaction. This was in Chicago. So, at that precise moment, matter lost continuity, as predicted by Dirac’s equation in nineteen hundred and twenty-eight, for our sins.

After that, it was still a matter of particles and antiparticles: a core, positive protons, negative electrons, neutrons, positrons, and unstable uranium on the verge of splitting, unsure whether to stay as it was or diverge beyond the point of no return. If a proton is brought nearer to a nucleus, their repulsion will increase. But forced to stay in close proximity with each other (if the critical mass reaches one kilo), the forces are reversed and the protons will penetrate the nucleus. As a result, once the potential barrier is crossed, repulsion becomes attraction, which holds true for all bodies.

Because mass is only one of the avatars of energy – as are heat, movement and work. Energy can change without fearing for its life and be reborn in a different form. Consequently, every kilo of precious stone, torn from the earth and carefully transported to power stations for containment, will be transformed into a billion kilowatt hours. Consider the lights of the city, the flash of a train through the January night along the wide river. Consider, you who sleep in peace, the billions of nuclei, protons and neutrons flowing past, like your bodies, still alive yesterday, in harmony with everything, then transmuted by a burst of radiance into heat and light.

Calculation: It was to handle the interminable calculations which were required by the Super to destroy the world that Johnny, with money from Lewis Strauss (who thought the machine could predict fine weather), built the first programmable binary computer at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study (whose director Oppenheimer was to become). This was MANIAC, a digital machine which broke with analogue dreams. It was conceived like the brain within the crucible of the Macy Conferences in the hope of controlling the flow of information the way William Harvey had subjugated blood, and of winning the cold war against the human race.

They’d already come a long way from the ineffable ENIAC, that obese electronic colossus gorged with tubes designed to calculate ballistic firing tables, reliable whatever the wind speed, in order to guide artillery and shoot down planes in any season, although it could be disrupted by a tiny insect. But they’d also come further than TRANSAC, the first transistor computer designed by Philco for the army in nineteen hundred and fifty-four, and the platform for the IBM 7090, which became the largest standard scientific computer in the world, equipped with a FORTRAN compiler, but already obsolete by the time Wilkes invented microprogramming.

Klara, Johnny’s wife and Françoise, Ulam’s wife, spent whole nights programming MANIAC’s double in Los Alamos. With uninformed hands, but with love (for this has always been the popular notion of women’s love), they fed their husbands’ thingamajig, without knowing the whys or wherefores of this endless embroidery of calculations (in the same way as I have no idea, sixty years on, how this MacBook Pro, on whose screen I’m typing these lines in memory of their faith, works or why). Because, as Fermi said, even the tallest tree on earth cannot touch the sky.

C. A History of Life

XXIV

Niels Bohr, 1885–1962 (Copenhagen–Copenhagen). Leo Szilard, 1898–1964 (Budapest– La Jolla). Enrico Fermi, 1901–1954 (Rome–Chicago). John von Neumann, 1903–1957 (Budapest–Washington DC). Robert Oppenheimer, 1904–1967 (New York–New York). Edward Teller, 1908–2003 (Budapest–Stanford). Stan Ulam, 1909–1984 (Lwow–Santa Fe).

And you too, the youngest, Klaus Fuchs, who died with your kin in East Berlin in 1988, at the age of seventy, a year before the wall came down, and with it what had become the reason for your lives, your causes, your walls, you survivors of other causes, other walls. None of you will know the walls of our time, built after you, or our causes, or our wars, we who were the children of your causes, your wars, and the destiny of your life’s work.

At the Cinéac des Ternes, the earth grinds to a halt. Bombs

and giant octopuses. Clusters of people in flight.

XXV

Dead among other dead, all that remains of you is your eternal work stationed in the silos, with the indifference of the ancient gods, ready to appear suddenly in the din of turbines.

But you are there, among us, mortals enslaved by the blind power whose ring you one day closed. Geniuses, who’d read everything, who spoke every language. True geniuses.

Evil spirits and blessed spirits, inlaid within the applied sciences, which count for nothing much, i.e. the fate of the world. Escapees from the ghettos of Lwow, Budapest, Warsaw, Wroclaw,

Destined for wisdom, study, beauty; for the Law sought outside the Yeshiva, in order to reveal it in dark matter and poetry which (according to Vico) contains our spiritual origins.

A tower of which nothing remains but the iron frame

on the razed ground of the punished town.

XXVI

John von Neumann in a wheelchair, receiving the Medal of Freedom from President Eisenhower. Ike face on and Johnny in profile,

His jaunty expression for the photo the same as when he used to ogle girls. His last public appearance, says the caption. Then, nothing, when back among us, mere mortals.

No public image of your decline, of your pallid face haggard with cancer on the tepid white hospital sheet; Of your fear, your wandering eye, your bloated stomach. Your ossified hands perhaps still gripping something. No matter. You, the salt of the earth.

Immense herd of oxen, driven towards the slaughter house.

The cries of the cattle traders.

XXVII

And even you Edward, man and daimon, what were you gripping? What was that thing cupped in your palm when your hands let go of everything, even the power to embody power.

The power to bring death, to let live and bring to life. Or nothing but the power to live, just a little longer, among the survivors shielded from disaster.

No matter. It doesn’t matter what it was, it doesn’t matter what the thing was, so long as it was peaceful, and it remembered the inhabited, burnt-out radiant towns. You, the archetypal survivors.

How peaceful your terrified heart is now, restored by death to the infernal glory of childhood. Unconscious, eyes closed in innocence.

Mum in tears, in the car, newspaper open.

The war, more widespread than ever, say the black letters.

The bombs more powerful, more fiendish than ever.

When I was just a child in school

I asked my teacher what should I try

Should I paint pictures ? / Should I sing songs ?

This was her wise reply / Que sera sera /

Whatever will be will be

The future’s not ours to see / Que sera sera.

Biographical Details

Oppenheimer: Julius Oppenheimer, from Hanau to New York, sold German textiles for the ready-to-wear industry. Seven hundred thousand sewing machines delivered every year, and a seventy-million-dollar contract. So Robert was born to wealth in Riverside Drive, a long way from the synagogues and market stalls. Why poetry, why not physics? Goethe loved chemistry and Robert, wooden-handed Ella’s Wonder Kid, shone, frail and bullied, naked in the icehouse, or watched the oceanic river flow past, alternating between poetry and differential calculus. Disgust of origins and the flesh laid bare on horseback in New Mexico on the mesa of Pajarito Mountain. Then the wanderings of the precocious lunatic. Hiding out in the Widener like – he said – a Goth pillaging Rome, where he devoured Poincaré and Bridgman, before fleeing to the Cavendish in Göttingen, where he lay in wait for a hydrogen atom which seemingly disobeyed classical mechanics beyond the potential barrier. Despite the devastation caused by quantum theory, he remained an underachiever, notwithstanding his promise, his wealth, the hype.

Szilard: the Szilard family weren’t always called Szilard, because they came from Galicia where the Jews were deprived of last names until Emperor Joseph II let them have German surnames. These they took to America, where they were arbitrarily changed by customs officers on Ellis Island into proper English like Silver, Gold or Black. However, it remains a mystery why Szilard stayed Szilard. Spitz, the surname, meaning summit, inherited by Leo’s grandfather, was lost in the mountains of Slovakia, and his widow, when she came to Budapest, changed Spitz to Szilard, meaning robust in Hungarian. There’s no rhyme or reason why surnames follow people then take flight, are given and taken back. But the new name took possession of the sons, turning them into engineers, and Leo’s father worked on the tramway. He, in his turn, fathered engineers, i.e. determined children who stayed curled up within the stories told by Tekla to teach them what truth was. Like the one about their grandfather who, when at school, acting out of dual loyalty, denounced his friends to the authorities, as he’d undertaken to do, then included himself among the culprits so that he was excluded too. Thereby illustrating the paradox of set theory which is as disturbing as first love.

Teller: Max, Teller’s father, was born in Ersekujvar, the market town where Jews traded absence at night for authorisation to appear by day. Ordinary bankers, good people, doctors, uncompromising lawyers. But Edward as a child wondered why they had to obey two laws, the Torah plus the secular set of rules. However, despite feet shackled by one law and hands tied by the other, they survived the camps, except for András, who died in nineteen hundred and forty-five. The year when his brother-in-law Edward first realised what he would do once America was in his pocket, and when he decided that Emma and Ilona would come to die at his side in a desert, if Stalin would let them leave, and if America managed to survive into the distant future. At the Minta Gymnasium, this mummy’s boy was teased for attempting to teach maths, to his maths teachers, because of his genius, naturally. Then later, having understood the meaning of the word justice, he knew how to meet threat with threat and create his destiny’s law without exception. After that, he left to study in Germany.

Ulam: Stan came from Lwow, Lemberg or Lviv, depending on the vicissitudes of war and the Go game played between princes, although none of this mattered to the boy. Dad was a lawyer and mum came from Stryj, where grandpa sold iron, mined in Galicia and the Carpathian Mountains. Sitting by the window with his father, he watched the Crown Prince pass by, then contemplated the figures in the carpet, knowing something his father didn’t. Then they were in Vienna, cheering on the Austrian army. After the war, they came back to live in Lwow, which was entered by Budenny’s cavalry (there was a horse named Babel), and he was saved by Pilsudski and attended the Gymnasium. Here, for the first time, he cheated, because each of his two eyes saw different things, making out numbers while the letters merged. Fascinated by the rings of Saturn, he wondered why Encke’s comet didn’t follow a regular path and discovered Poincaré in Polish – in the country where all his family and friends were to die, where his father burnt books to keep warm before being used to feed the flames in his turn.

Von Neumann: Max, Johnny’s father, a banker and poet from Galicia, made a wealthy marriage and was awarded a title by Franz Joseph. He put a tree in his living room on Christmas day, but still observed Yom Kippur, speaking, so they say, ancient Greek with his son, who learnt summas and cantos by heart from books which were once the pride and joy of a ruined country squire. He was then handed over to Laszlo Ratz, master of the theory of numbers, who every week knocked at the three-storey house on Zsilinszky Street (a discreet Mezuzah fixed to the doorframe), where Johnny was battling with axiomatic set theory, before escaping Béla Kun, then the enemies of Béla Kun and the Jews, whether they were rich or poor, law-abiding or rebellious. He fled to Germany and elsewhere, ending up in Princeton, where the Institute for Advanced Study had just been founded by the Bamberger family to breathe life and soul into the department store.

Appendix

The Salt of the Earth was written in June 2013 in response to works by the artist Angelika Markul.

The central text draws on a wide variety of books and documents I’ve collected out of interest over the years. These include numerous works devoted to the history of the Manhattan Project, but I’ll only list a few that were particularly useful: Ray Monk, Inside the Center: the Life of Robert J. Oppenheimer, Jonathan Cape Ltd, New York, 2012. Giorgio Israel, Ana M. Gasca, The World as a Mathematical Game: John von Neumann and Twentieth Century Science, Birkhauser Verlag, Berlin, 2009. Stan Ulam, Adventures of a Mathematician, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1976. Pap Ndiaye, Du nylon et des bombes. Dupont de Nemours, le marché et l’Etat américain, 1900–1970, Belin, Paris, 2001. Jeff Hughes, The Manhattan Project. Big Science and the Atom Bomb, Icon Books, Cambridge, 2002. Claude Delmas, La bombe atomique, Complexe, Paris, 1985. Michel Rival, Robert Oppenheimer, Paris, Seuil, 2002. Istvan Hargittai, Martians of Science, Five Physicists who Changed the Twentieth Century, OUP, Oxford, 2006. John Hersey, Hiroshima. Lundi 6 août 1945, 8h 15, Paris, Texto, 2011 (1946). Michel Rouzé, Oppenheimer et la bombe atomique, Paris, Seghers, 1962. And, last but not least, the delightful memoirs by Françoise Ulam: Françoise Ulam, De Paris à Los Alamos : une odyssée franco-américaine, L’Harmattan, Paris, 1998. Two types of fragments are inserted between the twenty-seven stanzas of the central text: The first (in italics) are drawn from personal memories dating from my childhood, particularly my earliest years, i.e. 1943–1947. These recollections, which are often confused and difficult to interpret, even for me, only exist now as recurrent flashes of memory or fleeting images. The second (in bold) are texts – in Spanish or in English – taken from popular songs in the years around World War Two, which might have been playing at the parties and dances at Los Alamos while the bomb was being built.

Translated by Sue Rose