“…physical Teleology, (…) if it did not borrow from the moral Teleology without being observed, but were to proceed consistently, could only found a Demonology…”

Immanuel Kant, “Critique of Judgement”

Force and affirmation

Something returns from the devil’s throat. Something primeval, returned to us with the devil’s vomit, something lurking within the oldest spume of our world. The waters are receding, together with the blackened remains of matter, at times resembling the undigested corpses of creatures difficult to identify. From the chasm of history return remnants of the past. We encounter just such an image, appealing and repulsive, fascinating and appalling, while watching Devil’s Gorge by Angelika Markul. In this installation of video and sculpture, the full force of the demonic power unleashed by the artist reveals itself. Markul’s art is a tool for, and a place of, liberation.

The most demonic aspect is probably the way Angelika Markul turns nature into art. And, more precisely, what happens to nature in her works of art. Nature is the subject matter of Markul’s work, only inversely to classical art where inanimate matter is transformed into mimetic manifestations of the animate. Here it is more about unleashing demons, or confronting demonised forces, which become captivating in Markul’s work.

Markul is interested in the precise moment that Immanuel Kant considered treacherous. As he argues in his Critique of Judgment, nature must be seen as purposive and its purposiveness must be linked with morality. If it were not so, emphasises the philosopher, the cognition of nature, any discourse about it (any attempt to formulate general claims about how the world functions, or to describe world phenomena with the use of notions), would be nothing other than demonology. Kant was right to say that when we deprive our thoughts of any reference to morality, we inevitably lapse into demonology. In Markul’s work, demonology is no longer what Kant was thinking about it, i.e. “an anthropomorphic way of representing the highest Being”.(1) Rather it could be described as closer to the way the demon was comprehended in ancient Greece, where any action understood as caused by supernatural power was defined as demonic, without yet inscribing this power in the distinction between good and evil. (2) The artist wants to reach this primal understanding but she does not stop there.

Markul immerses herself in the Devil’s Gorge in order to meet what is pre-purposive and pre-moral, for it is pre-human. Markul does this in order to find the power of nature, which does not fit in the purposiveness attributed to it by human reason, and is not subject to morality established by humans. This immoral, purposeless and inhuman power – terrifying in its omnipotence – has been demonised, equated with evil (certainly, but not only in Western

civilisation,) and as such had to be stifled in an attempt to subdue it. Angelika Markul’s work from the Devil’s Gorge regurgitates a mere semblance of what may return to us when the power – accumulated by centuries of suppression of what are perceived as demonic forces – breaks free.

The artist finds a manifestation of primary forces in a giant waterfall called the Devil’s Gorge, where the water falls from the height of 82 meters. It is part of the world’s highest set of waterfalls, Iguazu, extending in the shape of an elongated horseshoe for a length of 2.7 kilometres. It is also one of the oldest geological formations of the Earth. Angelika Markul goes there to meet a force possessing demonic (i.e. inhuman) powers, while the installation of video and sculpture created by her following this meeting, is an expression of affirmation of this force. Free from fear and resentment, the artist seeks what has been demonised as evil, appalling and diabolic. She daringly goes out to meet it, going on expeditions to places where these forces, once unleashed, have slipped completely out of control. Markul thoroughly approves of them, despite the fact that their release is often accompanied by destructive power, and its consequences are dangerous.

Such is the case in Fukushima, where modern demonism revealed its true power, which consists of forces of nature (primarily natural) and forces unleashed by man. The forces of an earthquake, of a tsunami, are combined with nuclear forces – the result of this combination is the landscape of destruction which is portrayed in a video recording entitled Welcome

to Fukushima, and in accompanying photographs.

However a place doomed to be abandoned may become a place of rebirth. This happened in the Exclusion Zone surrounding the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. The artist went on an expedition there and brought back an installation entitled Bambi in Chernobyl. The installation is immersed in white, with the white bodies of sculptures bearing testimony to what happened, and being both victims and survivors of the disaster. The bodies are placed in a structure which is an artistic interpretation of the infrastructure preserved on the original site. This abandoned zone is presented in the video part of the installation – it is filled with the vestiges of the erstwhile people who once lived there, while nature, though showing signs of damage and contamination, is permeated with a calmness and serenity. It is precisely this kind of peace and serenity that are the most demonic; they reveal the power of nature, which allows uninterrupted existence in a world abandoned by humans. The power of nature is pre-human and post-human.

Angelika Markul’s trip to Chernobyl in many respects resembles another trip to a forbidden zone – that presented by Andrei Tarkovsky in Stalker. The film is a poignant story about seeking the truth in spite of dangers that lie ahead. The main character in the title role, the Stalker – a guide or a smuggler hired to lead people safely through the Zone and all its dangers – ventures once again, despite his wife’s protests, into the forbidden and closely guarded zone in order to accompany the Professor and the Writer in their efforts to make sense of the world and of life. They travel through deserted areas and gloomy surroundings. Their destination is the mysterious chamber, which fulfils a person’s innermost desires. When the three of them arrive at the entrance of the Room, they stop at the threshold: the Stalker, who cannot go in, the Writer looking for inspiration, and the Professor, who arrived with a twenty-kiloton bomb and the intention to destroy the Room. With what will they return?

Return from the Zone and entering the cave

“You’re back!” – says the Stalker’s wife, when she meets the three men, pensive, sitting in the local bar. They returned, having never crossed the threshold of the mystery that separated them from achieving their goals. According to the Stalker, they lacked faith either in the mystery itself, or in the possibility of uncovering it, or perhaps in the need to acquire such knowledge – we will never know. The Stalker himself was full of faith but had lost it. He breaks down and his wife puts him to bed, hoping that sleep will bring him relief and solace. The relief and solace she herself is looking for, desperately and in vain. Neither husband nor wife notices their daughter, endowed with supernatural abilities.

Some of the similarities between both expeditions are striking; these very same aspects, however, further emphasise the differences. Angelika Markul also travels to the zone in search of the truth. The landscape she finds there could be a setting for Tarkovsky’s film, often considered a premonition of the Chernobyl disaster and its aftermath. In contrast to the characters of the film, Markul does not stop before the doorway, but boldly crosses the border. However, while also searching for truth, she is looking for something quite different than the characters in the film. She is not suffering existential torment about the meaning of life, or a fear of uncovering the secret that life makes no sense. She does not lack faith either – probably because what she is looking for gives her a strength that does not allow for any doubt.

Strength is a mystery and Markul greedily grabs at any manifestation of it, examines it and processes it into her work. This mystery is hidden though in a cave rather than in a room – in a cave meticulously created by the artist in the museum exhibition space. Having crossed the threshold of the exhibition space, visitors can meet the demons of contemporaneity captured and presented by Angelika Markul.

The artist ventures into the zone (whether in Fukushima or in Chernobyl) in order to enter the cave and bring it back to the viewers. Just like the Stalker, but unlike him and his companions who had stopped before the doorway and never entered, gripped by claws of powerlessness, Markul her audience enter the furthest depths (which triggers, as we shall see, some violence). Entering the cave equals confronting the myth – the old Platonic myth that keeps coming back to us. Recently this myth has been evoked mainly in order to emphasise the need to exit the cave. One of the weightiest concepts in which this need is supported and even radicalised – do not enter the cave! – is Bruno Latour’s idea of political ecology (3).

Despite this, Angelika Markul proposes descending into the depths of the cave – not in order to perform Plato’s shadow theatre, which would present the people imprisoned there the gleam of eternal ideas. The artist descends even deeper to meet with the demon of pre-human, post-human forces, over which we have no control, and which have no interest in us humans. The cave appears to have no bottom, it turns out to be a corridor leading to the other side of the world and reaching a place where this place is no more, but we are not elsewhere either.

Land of Departure

The video entitled Land of Departure depicts the Earth seeming to touch the sky, while the sky and the entire universe are inclined towards the Earth as if they were to connect. The mountainous line of the desert-like and completely dark landscape seems to be motionless, contrasting with the dynamic movement of celestial bodies in the sky. We feel at the same time that the mass of the Earth moves together with other celestial bodies, driven by physical forces that are too powerful for us to understand and which can be captured only with abstract calculations. With this seductive image, Angelika Markul creates a substitute for our sensation of the mighty power of these forces.

This feeling shows through the darkness of places where the use of artificial light is almost completely prohibited. One such place is the ALMA observatory in the Atacama Desert in Chile, yet another area into which Markul ventures in order to track the demons of extra-human forces. Markul’s cave turns out to be a hallway, but unlike the cave in Plato’s work, it does not lead to the blinding gleam of the world of ideas, but to distant silhouettes glistening in the dark, reflecting bodies that are infinitely farther from the Sun.

Angelika Markul’s demonology becomes possible, and probably necessary, after what Latour calls “the end of nature”(4). The unleashing of forces is one of the manifestations of nature’s death. Their demonic power is not paranormal, supernatural or supra-sensory; on the contrary it is ultra-natural, undeniable and pre-sensory – it cannot be construed within a notion of nature

understood moralistically and teleologically. On this point Markul seems to agree with Latour against Kant in rejecting a concept of nature as constructed by the sciences of Enlightenment. No demonic forces, purposeless and immoral, dwell there.

The Land of Departure is probably the work in which Angelika Markul reveals most overtly what her art is: the unceasing preparations for recurring departures and their constant affirmation. It is precisely where the artist finds the strength to confront the unleashed forces of the inhuman. How can she show them to us, or rather suggest their actions and power? How can she make them perceivable to our limited perception, which is unable to capture even what has been designed especially for our possibilities? All this is possible thanks to a specific form of violence, to which she tries to subdue these forces. Does this mean the taming of the demons?

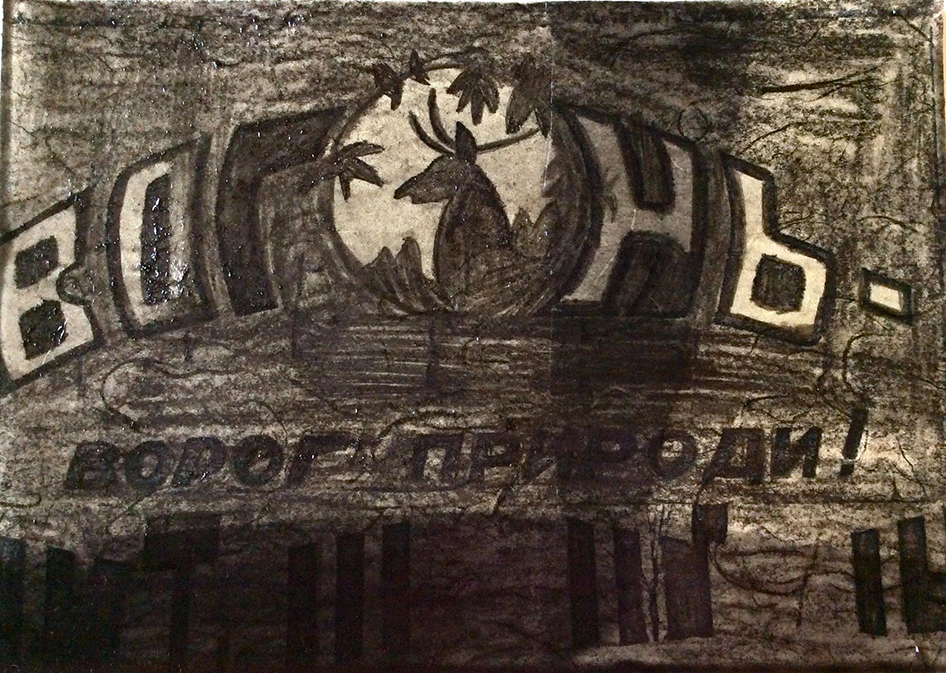

This seems to be suggested by a sculpture (untitled) made of a black lump of matter bound with rope, a deformed body of an unidentifiable creature. The figure becomes manageable. It is complemented by blurred wraiths appearing on a shiny black surface in four different places within the exhibition site – these are the viewers’ mirror reflections. The demon’s revelation in a classic, naive form; after all, this figure has been invented by man and only man can embody it. What becomes tamed and manageable is an anthropomorphic demon, and this is for at least two reasons. Firstly, though less importantly: this demon is guilty of destroying nature. The second reason shows there is a lot more at stake: the anthropomorphic demon must be tamed, because the forces of what is inhuman or supra-human must be unleashed. If this does not happen, we remain within the range of naive demonology (that which Kant warned against). However Angelika Markul is concerned with a very different kind of demonism, one we have to confront through a specific kind of violence.

Aesthetic violence

At first glance it might seem that these works created by Angelika Markul oscillate between the aesthetics of beauty and sublime. As a consequence their audacity comes from crossing the border, established by Kant, between beauty and beauty-seeking art on the one hand, and nature and nature-related sublime on the other. In fact, even if these works of art produce the effects characteristic of either aesthetics, these manifestations are of a rather secondary nature. They cannot be pigeonholed as belonging to the classical doctrine of beauty, as they would have to be embedded in a moral order (as “the Beautiful is the symbol of the morally Good” )(5). The issue of the sublime is more complex; according to Kant this feeling is born “in our mind, in so far as we can become conscious that we are superior to nature within”.(6) The superiority is needed in order to overcome fear; the sublime may appear when, seeing something as terrifying, we are able to overcome this fear. The question of violence is crucial here: “Might is that which is superior to great hindrances. It is called dominion if it is superior to the resistance of that which itself possesses might. Nature considered in an aesthetical judgement as might that has no dominion over us, is dynamically sublime.”(7) This means that man is as powerful as nature, for he does not have to fear its power and can give himself over to a feeling of sublimity, while looking at the raging sea and billowing storm clouds…

We can repeat after Latour that with the end of nature, the power of nature and the power of man come to an end as well. By contributing to the end of nature, man has destroyed his own might, born out of resistance against nature. The sublime in this context would be impossible, because there is no situation in which one can regard a given phenomenon as fearsome without being afraid. The paradox of Angelika Markul’s demonology is the lack of fear, which does not stem however from desensitisation. Still, it would be impossible to talk about demonism if there was no threat of violence. The forces which the artist squares up to are demonic, for they are ultra-natural, undeniable and pre-sensory, and therefore powerful and overwhelming. One cannot confront them except through a different kind of violence that must be called aesthetic. It does not arise from a clash of powers, from which, as Kant argues, human reason always comes out victorious. Nothing human can be more powerful than the omnipotence of the unleashed forces of what is extra-human and extra-terrestrial. The fear that can be aroused in the confrontation must be overcome, for it inevitably leads to powerlessness. Aesthetic violence is a way of overcoming fear, in which, by some paradoxical gesture, fear is dispelled not by desensitisation, but through involvement in a game of fascination, thus becoming an element of affirmative hypersensitisation.

Only hypersensitisation opens up possibilities for discerning something creative in the scenery which Angelika Markul unfolds before us – especially in the installations of painting and sculpture in which she exposes a blackened corporality. The body of the Earth does not appear as one of the celestial bodies, but reveals its dark organic nature, saved from destruction and disintegration only by the artist’s activities. It illustrates the state of the world after the death of nature, while at the same time creating a new concept for this condition. This concept seems to be utterly opposite to an idea developed by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari on the eve of nature’s death. In their vision, the body without organs (earth, capital) had been colonised and exploited by greedy machines in the process of a continuous production that had made it possible for primitive cultures, feudalism and capitalism to exist. However, in fact, it was the interminable and inexhaustible corporality of the Earth that guaranteed maintaining and developing the desired level of production. In Markul’s work what remains of the body of the Earth are merely its organs (which did not exist in Deleuze and Guattari (8) – representing the remnants of a nature that has been destroyed (nature can probably revive itself in its wild and untamed nature, as it did in Chernobyl). Along with nature’s death ended the metaphysics of what was supernatural and supra-sensory; what remains is merely the physics of forces (representing the ultra-natural and sub-sensory). We can see its manifestations only through this aesthetic violence and affirmative hypersensitivity.

In this context, the sound piece Help cannot be understood as a rescue call. It is rather about posing the following question: Who, in this inhuman and post-natural world, can call for help and expect it to arrive? The only possible answer to this could be the overwhelming silence of another installation, created with paintings made of waxed leather tightly covering the walls.

A final hush.

Translated by Monika Fryszkowska

(1) Emmanuel Kant, Critique of Judgement, The haffner library of classics, new York, 1951, p. 310.

(2) Georg luck, Arcana Mundi: Magic and the Occult in the Greek and Roman Worlds: A Collection of Ancient Texts, The johns hopkins university press, Baltimore 2006, p. 207. cf. also Britannica Encyclopaedia of World Religions, Encyclopaedia Britannica, inc., chicago – london – new delhi – paris – seoul – sydney – Taipei – Tokyo 2006, pp. 286-287.

(3) Bruno latour, Politics of Nature: How to Bring the Sciences into Democracy, tr. by Catherine Porter, Harvard university press, cambridge, Mass., usA, 2004.

(4) ibid.

(5) kant, Critique of …, op. cit.

(6) ibid.

(7) ibid.

(8) Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, Capitalism and Schizophrenia: Anti-Oedipus, tr. by robert hurley, Mark seem, and helen r. lane, university of Minnesota press, Minneapolis, 1983. Katalog Angelika Markul:Layout 1 11/27/13 1:38 PM Page 64