One is under the impression that an abyss of time opens up right before our eyes, from which mysterious traces, terrifying relics and poignant images emerge. Alongside footprints of dinosaurs living 147 million years ago there are the remains of an animal that went extinct about 11,000 years ago or afterimages of a hundred-year-old photograph. All of them add up to form a dreamlike constellation. Mythology is intertwined with archaeology, ethnography with palaeontology, and history with fantasy, creating a unique experience of time.

Angelika Markul is extremely consistent in developing a poetics of dream to explore those dimensions of time that elude both common experience and scientific theories. She has come up with her own formula, in which dreamtime and deep time become dimensions of the present, enabling certain symbolic reversals.

While earlier in her practice she would protest against past violence by resorting to a kind of aesthetic violence, nowadays she trusts the power of poetics. She is able to do so by employing her own method of bearing witness.

Dreamtime

A patch of land is visible not even from a bird’s eye view, but rather from some distant, cosmic perspective. The overall view shows the seashore with fragments of land, sandy beaches and white-capped waves alternating at regular intervals. At first glance, the regular composition of shapes and intricate combinations of colour could be mistaken for an abstract painting. The entire film entitled Marella is based on such ambivalence – the measured aesthetics of each shot every now and then turns out to capture the actual landscape, seemingly unrealistic due to the refined colour composition. This surprising game is interrupted by even more unexpected close-ups of shapes that could be recognised as imprints of animal feet.

The film was shot on the coast near Broome, Australia, where traces of potentially the most diverse ichnofauna in the world were discovered. Scattered over an area of 100 kilometres, the footprints are preserved in sandstone from the Lower Cretaceous period (100.5-145 million years ago). The artist focuses mainly on the imprints of three-toed feet, the smaller of which were left by the species Megalosauropus broomensis (“big lizard foot of Broome”). However, in this case, palaeontology is but a starting point for building a vehicle that can take us back to ancient times.

Mythology has a similar function, although it can lead to metaphorisation. The title of the film makes a reference to an Aboriginal myth. Marella, or Marala, is the name of the Emu Man, considered by the Australian tribe of Gooralabooloo to be the creator of their land in the Dreamtime. For all Aboriginal tribes, the Dreaming or Dreamtime is the period in which the world was created and given rules, in which the ancestors live, from which everything emerges and to which everything returns. It is a transcendent realm in a timeless past, to which, however, one can connect and where one will eventually return. Therefore, this is not the past in the sense of something gone forever, as it is understood in our culture with a linear concept of time.

The stars of the Milky Way viewed from the southern hemisphere form the outline of the Emu Man. The perspective adopted in the film is therefore his point of view. Marella looks at the traces left by his three-toed feet. The film takes us to the Dreamtime, where earth, water, sky and space meet. The Aboriginal myth is translated into an experience that is comprehensible to us. The artist makes a different, unknown time sphere accessible to the viewers. Like in the myth, the past is not gone – it can be accessed by means of an aesthetic experience enabled by art.

Deep time

What the Gooralabooloo people believe to be Marella’s footprints has been identified by palaeontologists as traces of Megalosauropus broomensis. Markul is fascinated by the sculptural quality of the ichnofossils – not only does she film the prints, but also uses them to obtain sculptural forms. She does the same with traces of other dinosaurs or plants – she creates artistic relics out of them.

It is connected with her previous practice of creating sculptures intended as remnants or artefacts to be excavated in the future. In this way, she adopts the perspective of reversed archaeology in order to enable us to observe our everyday life from a future point of view, imagine what traces will be left by our present existence.

The artist extended this principle of reversal when she worked with the remains of Mylodon, a genus of ground sloth that went extinct around 11,000 years ago. On the basis of the preserved fossils, scientists have been able to simulate visualisations of the possible appearance of this animal. Markul, however, has no need for their findings. In her sculpture, she endows the remains with a new body – a phantom body in which the animal does not return to us as an image of something that used to exist, but as an artificially created relic. Science is drawn into the game again – this time as taphonomy, the study of the posthumous fate of organic remains.

Markul’s sculptures are the gateway to the deep time, but in the form of a current experience. The notion of deep time refers to the impossibility of comprehending periods spanning millions of years, which make the entire history of mankind resemble a thin film on top of an abyss of the geological past. Deep time is absolutely incommensurate with human time.

But here the artist stages a situation in which we are able to come face to face with an artefact showing the remains of a creature that is believed to have lived in the period from 2.58 million to approximately 11,000 years ago. This imaginative and speculative opening allows us to transcend the limits of human time and the tyranny of the present moment, as if a crack appeared before us through which we could peek into deep time.

Phantom testimonies

Dreamtime morphs into deep time, but for Angelika Markul it is not about bending or shifting time, but bearing witness in spite of time.

In the case of the sculpture called Mylodon, the artist endowed an animal we know from fossil records with a phantom body not in order to make its past existence more real, but to bear witness to its disappearance. This is a permanent feature of her artistic practice. She travels to the scene (to Broome in 2019 or Chernobyl in 2013, to give just two examples) in order to bear witness through her subsequent works of art, or more precisely, through the aesthetic experience enabled by the works.

A special example of this practice is the set of sculptures belonging to the series of works entitled Tierra del Fuego. The shapes, resembling deformed heads, are actually phantoms created on the basis of photographs of members of the Selk’nam tribe during ritual ceremonies, taken by Martin Gusinde a century ago. The pictures show painted bodies, faces covered with masks or distorted by special headwear. The depicted forms trigger associations with the most avant-garde gestures of modern art.

Gusinde was a missionary and researcher who was accepted into the Selk’nam tribe – this is how he managed to make this fascinating photographic documentation in the 1920s. The tribes that had inhabited Tierra del Fuego for thousands of years fell victim to gold diggers, who invaded the archipelago in the late 19th century and decimated the indigenous population. The last Selk’namans died in the second half of the 20th century.

Angelika Markul has no intention of reconstructing the forms from Gusinde’s photographs; on the contrary, she creates a set of phantom heads that resembles a trophy cabinet proving the extermination of a people. She reverses ethnography – instead of presenting us with documents about an extinct culture, pretending to offer knowledge about it, all that she creates is an embodiment of loss that will haunt us with phantom pains.

The encased sculpture belonging to the Tierra del Fuego series of works is dedicated to all tribes inhabiting the eponymous patch of Argentinean and Chilean Patagonia. The artist wants to display fabricated remnants of destroyed cultures – her artistic taphonomy is a means of reversing archaeology and ethnography.

Chronological plane

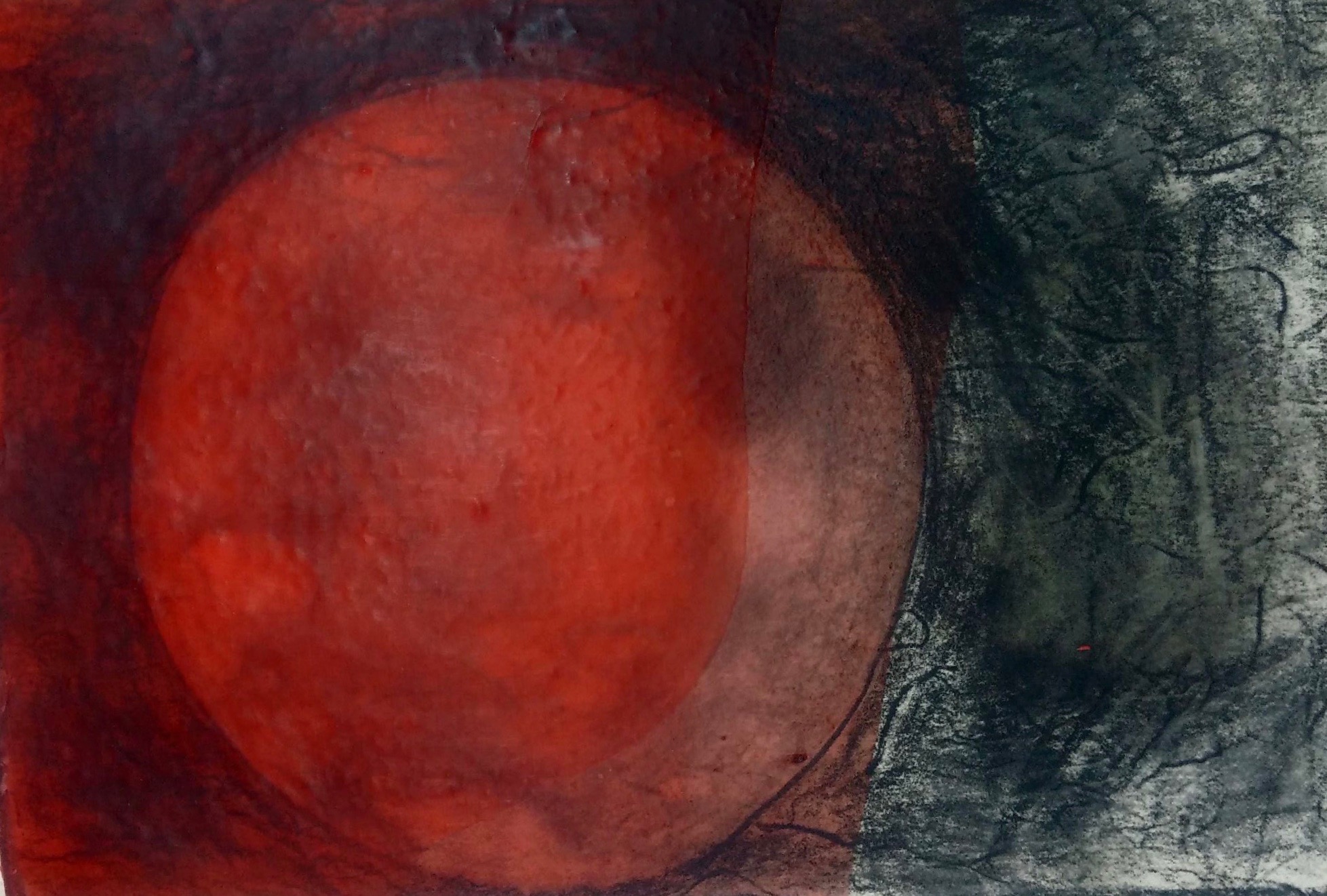

In the simplest terms, the two paintings of Tierra del Fuego are poetic representations of this strip of land at the end of the world. However, they can also be interpreted as illustrations of how time is experienced in Markul’s art. The mythological dreamtime and geological deep time have been stratified so that their unimaginable depths are stretched into bits that can be perceived by the senses. They become imagined depictions that make encounter possible, even without guaranteeing full comprehension. Thanks to this, time ceases to be an abstract concept and acquires material tangibility.

Angelika Markul uses her vehicles to mould time, as if it was a malleable matter.

References

Bęben W., Aborygeni, pierwsi nomadzi. Życie i kultura, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Gdańskiego, Gdańsk 2021.

Gusinde M., The Lost Tribes of Tierra del Fuego: Selk’nam, Yamana, Kawésqar, Thames and Hudson, London 2015.

McPhee J., Basin and Range, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York 2000.

Salisbury S., et al., The Dinosaurian Ichnofauna of the Lower Cretaceous (Valanginian–Barremian) Broome Sandstone of the Walmadany Area (James Price Point), Dampier Peninsula, Western Australia, “Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology”, 2016, 36:sup1

Szyjewski A., Mitologia australijska jako nośnik tożsamości, Nomos, Kraków 2014.